The Atomic Turtle: Illusions During the Cold War Nuclear Crisis

- Alex Zhang

- Sep 3, 2025

- 15 min read

When the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic device in 1949, the US government faced the problem of governing a population suddenly aware that nuclear warheads could arrive without warning.[1] The Truman administration’s answer was the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FDCA), formed in 1950 to teach Americans how to “survive” nuclear war.[2] Over the next decade, the FCDA blanketed the nation with pamphlets such as The Family Fallout Shelter, classroom films like Duck and Cover, and nationally synchronized drills across schools.[3],[4] Civic leaders exhorted citizens to build backyard fallout shelters, while corporations rushed to market canned-ham survival packs and pre-cast concrete bunkers. Even the home itself became a weapon in America’s psychological Cold War arsenal; it was re-imagined as a sealed fortress stocked by diligent mothers.[5] Yet, classified assessments by military scientists quietly conceded what many citizens suspected: the advertised protections were largely illusory.[6] Civil defense in the 1950s, though disguised as a set of pragmatic safety measures, was in reality far from effective against nuclear weapons. Nonetheless, government publications, shelter blueprints, Congressional hearings, popular media features, and protest leaflets were distributed promising citizens of the United States safety in the case of a nuclear attack.[7]

Through framing nuclear survival using scientific language, the domestication of the nuclear threat by correlating it to more familiar and preventable dangers, and the staging of nationwide drills as civic ritual, 1950s U.S. civil defense transformed nuclear annihilation into an everyday routine. While that transformation reinforced patriarchal domestic roles and stoked consumer spending, it also demanded public displays of loyalty. This agenda revealed how Civil Defense offered Americans the comfort of illusory control by both domesticating the threat and empowering citizens with repetitive yet futile drills, fostering public acceptance of living under the shadow of nuclear annihilation, which was a necessary precondition for maintaining the nation’s unity and deterrence stance.

By framing nuclear survival in the seemingly objective language of science, 1950s U.S. Civil Defense (CD) materials stripped the FCDA of political controversy and muted opposition by portraying federal guidance as the product of research, granting Americans a reliable entity to trust. This type of propaganda was especially prevalent in the civil defense pamphlet The Family Fallout Shelter, which opens with a declaration from the National Academy of Sciences, stating, “Adequate shielding is the only effective means of preventing radiation casualties.”[8] The mention of the National Academy of Sciences created an aura of expertise around this document, borrowing the credibility of science to frame the shelter construction campaign as apolitical and a scientific necessity for safety. The pamphlet continued this strategy, asserting, “Your Federal Government has a shelter policy based on the knowledge that most of those beyond the range of blast and heat will survive if they have adequate protection from fallout,” coupling federal authority to the certainty of scientific “knowledge.”[9] Using the credibility of science allowed Government-sponsored information to be seen as science, granting false credibility to Civil Defense and giving Americans the calming consolation of the seemingly all-knowing FCDA.

Moreover, the Government-sponsored film You Can Beat the A-Bomb established its authority through visual performance and employing actors, projecting an image of scientific expertise and trustworthiness onto the FCDA. In the opening scene, an actor playing a white-coated scientist calmly measures the “everyday” radiation from a wristwatch with a Geiger counter for a janitor while teaching the janitor about radium’s radiation.[10] The following explanation of how a Geiger counter worked served to add more credibility, making Civil Defense seem scientifically educated and thus trustworthy.[11] The film then addressed fears surrounding nuclear weaponry and its effects, such as sterility, by claiming that the chances of radiation inflicting reproductive harm are “one in a million,” then presenting allegedly scientific shielding data for radiation, transferring the objectivity of statistical analysis onto the government’s agenda.[12] The reliance on scientific imagery and numbers was a strategy to manage public fear, as seen in the presentation of the FCDA agenda of preparedness as a series of rational actions guided by expert knowledge, giving the government both credibility and US citizens a reliable figure to trust in times of crisis.

To weave nuclear readiness into American life and blunt the paralyzing terror of atomic war, civil defense messaging domesticated the bomb’s horror by comparing it to familiar and manageable dangers, offering the illusion of control, which in turn allowed smoother psychological adaptation to the nuclear crisis. This comparative logic sought to recast the fear of nuclear weaponry as similar to events preventable by routine safety measures, making fallout preparations seem no more abnormal than preparing for a storm. In The Family Fallout Shelter, for example, readers are told that shelters “can serve a dual purpose—protection from tornadoes and other severe storms in addition to protection from the fallout radiation of a nuclear bomb.”[13] Equating nuclear apocalypse with natural disasters, for which households already possessed response measures, normalized the threat and implied that similar practical measures for a nuclear bomb would be enough. In a similar vein, the atomic scare film You Can Beat the A-Bomb further diminished the danger of atomic power by both comparing atomic weapons to ordinary objects like wristwatches and describing atomic energy as one more step in humanity’s technological ascent.[14] The film diluted the dangers of atomic weaponry by analogizing the bomb’s destructive capabilities to electricity’s relationship with the electric chair, implying that it is deadly but ultimately tamed, understood, and well-controlled.[15] By consistently comparing the unimaginable danger of the nuclear bomb to the familiar and controllable, civil defense authorities managed public emotion and integrated the nuclear threat into everyday life. This artificial perception provided the psychological comfort of illusory control, which was necessary for fostering public acceptance of living under the shadow of annihilation and maintaining the nation’s unity.

In addition to associating the threat with lesser dangers, U.S. Civil Defense planners tamed the danger of nuclear annihilation through the conversion of atomic survival into DIY projects and choreographed civic drills, channeling the nuclear crisis into manageable tasks that supplied a soothing but illusory sense of personal agency. The American domestic landscape of the 1950s was primarily characterized by the rise of the DIY rhetoric, where home-based construction and repair became a popular and often male-gendered way for demonstrating competence and strength and achieving personal fulfillment.[16] This preexisting enthusiasm for self-sufficiency within the home provided a framework that Civil Defense could easily take advantage of. Civil Defense’s exploitation of this rising DIY enthusiasm was especially prevalent in The Family Fallout Shelter pamphlet, which offered a checklist of standard safety supplies captioned “YOU SHOULD HAVE THE FOLLOWING ITEMS ON HAND AT ALL TIMES,” morphing post-attack survival into just another weather-like event.[17] The pamphlet explicitly linked shelter construction to the DIY rhetoric, noting that one shelter plan “has been designed specifically as a do-it-yourself project,” casting the job as an ordinary home-improvement effort.[18] This recasting was a deliberate effort to combine the existing home improvement enthusiasm with family safety and nuclear deterrence, transforming the home into an FCDA-sponsored project.[19] In addition, the pamphlet cut down the dangers of radiation to a simple and actionable principle: “Any mass of material between you and the fallout will cut down the amount of radiation that reaches you. Sufficient mass will make you safe.”[20] Reducing radiation to the acquisition of “sufficient mass” transformed a dangerous, scientific problem into a construction-based solution that aligned directly with the promoted DIY spirit, prompting Americans nationwide to purchase and stock up on survival supplies, boosting American economic activity.

Beyond the individual DIY project, civil defense extended this domestication of the nuclear crisis by staging survival as a civic ritual through mass media and public exercises, providing a routine that US citizens could rely on in times of crisis. FCDA films like the You Can Beat the A-bomb further translated nuclear survival into a household drill, depicting families performing prescribed steps to lock down the home, namely seeking designated safe spots like basements and inner rooms, covering windows, assuming the “duck and cover” posture, performing post-blast cleanup, washing, and relying on radio bulletins.[21] The film’s orderly checklist of actions mirrored the era’s emphasis on the home as a self-sufficiently manageable environment, revealing how the FCDA took advantage of the preexisting DIY and self-reliant rhetoric to reduce nuclear warfare to a series of tidy housekeeping assignments and comfort US citizens. As Penn State librarian Brett Spencer argued, these routine procedures helped US citizens “cope with the emotional distress and cognitive dissonance engendered by the constant threat of an attack.”[22] Through these prescribed household and individual routines, the FCDA reassured US citizens that disciplined routine was the key to survival, transforming the national fear of the crisis into a familiar domestic belief that if the household executed its assigned chores, the country would survive.

On top of emphasizing the DIY rhetoric, the FCDA focused its aforementioned propaganda on children. By reducing a horrifying threat to a set of catchy, cartoonish instructions, civil-defense propagandists embedded their nuclear crisis agenda into US citizens from early childhood, simultaneously dampening collective anxiety and strengthening national unity. Civil defense officials understood that the surest way to normalize the unthinkable was to teach it during childhood, and Duck and Cover became the template.[23] The film’s protagonist, Bert the Turtle, never utters a word of scientific explanation; instead, he survives a monkey’s stick of dynamite by performing a repeat-after-me maneuver while a jingle seals the lesson in memory, infantilizing the nuclear warhead by analogizing it to a cartoon explosive and implying that a nuclear attack was survivable simply by “ducking and covering.”[24] The film’s live-action segments extend the infantilization, branding the bomb a “new danger” but pairing it with fire and traffic accidents, correlating atomic annihilation to dangers society already mitigates via drills and rules that children can easily follow.[25] Even the bomb’s searing radiation is trivialized with a comparison to “a terrible sunburn,” muting its lethality and the danger of nuclear radiation.[26] The FCDA nationally encoded rhythmic, visual, and repetitive cues into children before they mastered logical reasoning. As a result, the agenda of Civil Defense was ingrained into the memory of the nation’s most vulnerable audience, ensuring their loyalty to the government and reinforcing the national unity of the next generation of Americans.

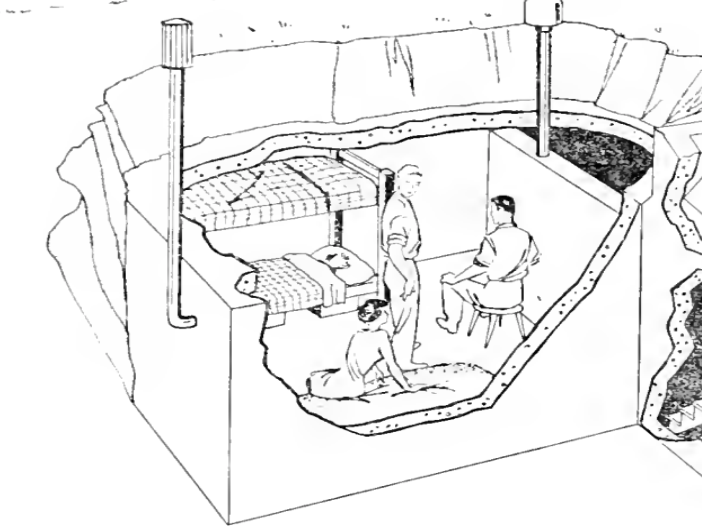

In addition to being targeted toward children, the FCDA’s agenda was also heavily gendered. Civil defense initiatives reinforced traditional masculinity by assigning men the primary responsibility for shelter construction and family protection, making the fear of nuclear war into a set of “masculine” tasks, reinforcing the patriarchal family structure deemed essential for national stability and public acceptance of the Cold War. Civil Defense materials consistently presented men in active, directive, and constructive roles, especially in shelter construction materials. The cover of The Family Fallout Shelter pamphlet, for example, depicts a man laying concrete blocks, an image replicated in numerous diagrams within, showing men as the primary builders and technical managers of these domestic fortresses.[27] Furthermore, the depictions that included both women and men, as seen in figures 1, 2, and 3, depicted the women sitting and the man dominantly upright, subtly implying male dominance and reinforcing the patriarchal family structure. In addition, the government film You Can Beat the A-Bomb more explicitly depicted the father directing the rest of the family during attack drills, cementing his position as the head of the household in crisis.[28] These portrayals strategically exploited masculine impulses to demonstrate competence, protectiveness, and technical skill, which were qualities intrinsically linked to American ideals of manhood, to give families a routine and plan to deal with the nuclear crisis.[29] The traditionalism of the gender roles further served as comfort to American citizens, reinforcing a known hierarchy that gave a sense of security and familiarity.

On the other side of gender roles, Civil Defense framed women’s roles in housekeeping and caregiving as vital to nuclear preparedness, reaffirming gendered normalcy and offering women a defined, psychologically manageable sphere of action. While men were tasked with building shelters, women were expected to govern life inside the bunker. The Family Fallout Shelter quietly emphasized that split, stating “Families with children will have particular problems… After the family has settled in the shelter, the housekeeping rules should be spelled out by the adult in charge,” effectively naming the mother chief of order within the domestic sphere.[30] Her duties of food rationing and child care were extended into the circumstances of a fallout shelter, perpetuating gender stereotypes, and as historian Sarah A. Lichtman put it, “literally building them into a concrete form.”[31]As the domestic sphere became more involved in atomic planning, especially in the shelter construction campaigns, women’s roles became more essential to civil defense.[32] As a result, the messages of civil defense were often directed toward women as housewives, caregivers of their families.[33] The assignment of gendered responsibilities in the context of a shelter traditionalized the nuclear threat, providing US citizens with the illusory comfort and control over the nuclear crisis they needed to keep national unity.

On top of the implied gender roles, the FCDA utilized consumer capitalism to push its agenda as well. By framing shelter construction and supply stockpiling as acts of responsible citizenship achievable through consumer purchases, civil defense effectively “marketed” nuclear preparedness, transforming existential anxiety into familiar consumerism, which provided a tangible but superficial way for individuals to assert control over their safety. The false control normalized the nuclear threat within everyday life and supported the national psychological mobilization for the Cold War. The government’s push for private shelter construction presented preparedness not just as a logical safety measure but as a civic duty that could be fulfilled through expenditure. The Family Fallout Shelter pamphlet sold safety as something one could buy. Its plans ranged from a budget “Basement Concrete Block Shelter” to the state-of-the-art underground bunker, with the text reminding readers that costs drop “if a shelter is constructed at the time a house is being built.”[34] This framing explicitly linked financial investment with safety, subtly encouraging a form of consumer citizenship where protection was purchasable. The pamphlet further emphasized that “No matter where you live, a fallout shelter is necessary insurance. … It will not be needed except in emergency. But in emergency, it will be priceless—as priceless as your life.” By framing fallout shelters as necessary for survival, this pamphlet reframed the acts of buying and building as an act of love to one’s family, weaponizing parental protectiveness. Federal authorities further fused consumer capitalism to shelter construction, subsequently presenting shelters as commodified “dream space[s]” rather than bunkers for protection.[35] This marketing of citizenship reframed the connotation of nuclear fallout survival and, just like the aforementioned DIY shelter shopping list, encouraged citizens across the nation to spend money on shelter construction and supplies, increasing consumerism in the US.

As well as the encouragement to spend money, the repetitiveness and reinforced concepts of the civil defense drills and preparedness campaigns functioned as a demand for public displays of loyalty, creating rituals that reinforced national unity and conformity to government command; this reinforcement of government power gave the central government and civil defense almost authoritarian control over the loyalties of the citizens of the US. The repetitive nature of messages like those in Duck and Cover, where the narrator explicitly commanded the audience, “He did what we all must learn to do…You…and you…and you!” framed loyalty as both a safety measure and a collective civic responsibility.[36] The film’s depiction of drills across diverse scenarios in scenes involving schoolyards, streets, and school hallways reinforced the idea that this conforming behavior was an omnipresent expectation to follow the national preparedness strategy.[37] The expectation of immediate action upon seeing the flash, regardless of the situation, cultivated a trained reflex that symbolized unquestioning compliance with the civil defense regime.

Adherence to civil defense procedures was further emphasized by the civil defense film Alert Today, Alive Tomorrow, but with a different repetition.[38] The film rooted civil defense in the ideal of “neighborliness,” implicitly equating participation in civil defense agendas with good citizenship and community responsibility, so that not participating or dissent appeared un-American.[39] Building upon the credibility gained from alleged scientific expertise, the positivity associated with “neighborliness” was transferred to the FCDA, giving civil defense the aura of a good neighbor, making its agendas harder to reject. Its abrupt shift from scenes of a peaceful neighborhood to a mushroom cloud, followed by civil defense instructions, served to create immediate fear and a need for a resolution provided by the FCDA, forcefully linking national survival to loyalty to US civil defense. The narrator further emphasized the importance of spreading the FCDA’s message, claiming that “since the program depends upon the degree of success in signing up volunteers, it is important to put the CD message before as many people as possible. The campaign must be widespread and hard-hitting.”[40] This emphasis directly commanded US citizens to advertise for the FCDA, framing the nuclear defense program as a volunteering opportunity and a chance to express one’s goodwill in the name of protecting the nation. Subsequently, this framing generated an obligation to endorse civil defense, turning participation into a badge of patriotism. The orchestrated unity within these Civil Defense materials reinforced the unity and conformity across the nation, but also contradicted the classic American ideal of individualism.

The FCDA’s defense goals were never about beating or surviving the bomb itself; their aim was surviving the idea of the bomb. By wrapping survival in the gloss of science, comparing atomic dangers to household hazards, and converting drills into civic ritual, the FDCA framed the nuclear crisis as a set of chores that a father could build, a mother could stock, and a child could rehearse. Subsequently, they reinforced patriarchal domestic roles and fused safety with shopping, teaching Americans that responsible citizenship could be bought in brick and canned ham. The choreography of comfort never promised real protection; its true purpose was to supply an illusion of agency strong enough to steady a nation asked to live under the threat of the bomb. The FCDA knew of the human vulnerability of comfort; it knew of how the familiar always appears safe, even under threats as detrimental as the nuclear bomb. So, Civil Defense exploited that reflex, revealing how easily authority can harness ritual, expertise, and commerce to domesticate fear and bind a nation to war agendas. When horror beyond comprehension is present, comfort often matters more than facts, and the promise of control, no matter how illusory or symbolic, can steady an entire nation.

Bibliography

Barker-Devine, Jenny. “‘Mightier than Missiles’: The Rhetoric of Civil Defense for Rural American Families, 1950-1970.” Agricultural History 80, no. 4 (2006): 415–35.

Brown, JoAnne. “‘A Is for Atom, B Is for Bomb’: Civil Defense in American Public Education, 1948-1963.” The Journal of American History 75, no. 1 (1988): 68–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/1889655.

Federal Civil Defense Administration. Alert Today, Alive Tomorrow. Washington, DC: Federal Civil Defense Administration, 1956. Directed by Larry O’Reilly. Film. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xoNC-MmiMqw.

Federal Civil Defense Administration. You Can Beat the A-Bomb. 1950. Film. Washington, DC: Federal Civil Defense Administration.

Federal Civil Defense Administration and National Education Association. Duck and Cover. Directed by Anthony Rizzo. 16 mm film. 1951. Washington, DC: Federal Civil Defense Administration and National Education Association.

Lichtman, Sarah A. “Do-It-Yourself Security: Safety, Gender, and the Home Fallout Shelter in Cold War America.” Journal of Design History 19, no. 1 (2006): 39–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3838672.

Masco, Joseph. “Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society.” Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 13–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41203538.

Northcutt, Susan Stoudinger. “WOMEN AND THE BOMB: DOMESTICATION OF THE ATOMIC BOMB IN THE UNITED STATES.” International Social Science Review 74, no. 3/4 (1999): 129–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41887009.

Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization. The Family Fallout Shelter. Pamphlet MP-15. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, June 1959; reprinted November 1959.

Oakes, Guy. “The Cold War Conception of Nuclear Reality: Mobilizing the American Imagination for Nuclear War in the 1950’s.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 6, no. 3 (1993): 339–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20007095.

Spencer, Brett. “From Atomic Shelters to Arms Control: Libraries, Civil Defense, and American Militarism during the Cold War.” Information & Culture 49, no. 3 (2014): 351–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43737397.

Winkler, Allan M. “The ‘Atom’ and American Life.” The History Teacher 26, no. 3 (1993): 317–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/494664.

________________

[1] Susan Stoudinger Northcutt, “Women and The Bomb: Domestication of the Atomic Bomb in the United States,” International Social Science Review 74, no. 3/4 (1999): 130, JSTOR.

[2] Northcutt, “WOMEN AND THE BOMB,” 130.

[3] Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, The Family Fallout Shelter, Pamphlet MP-15 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, June 1959; reprinted November 1959).

[4] Federal Civil Defense Administration and National Education Association, Duck and Cover, Directed by Anthony Rizzo, 16 mm film, 1951 (Washington, DC: Federal Civil Defense Administration and National Education Association).

[5] Sarah A. Lichtman, “Do-It-Yourself Security: Safety, Gender, and the Home Fallout Shelter in Cold War America,” Journal of Design History 19, no. 1 (2006): 39, JSTOR.

[6] Joseph Masco, “Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society,” Anthropology Now 1, no. 2 (2009): 13, JSTOR.

[7] Northcutt, “Women and The Bomb,” 133.

[8] Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, The Family Fallout Shelter, Pamphlet MP-15, 1.

[9] Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, The Family Fallout Shelter, Pamphlet MP-15, 2.

[10] Federal Civil Defense Administration, You Can Beat the A-Bomb, 1950, Film (Washington, DC: Federal Civil Defense Administration), 0:36-1:00.

[11] Federal Civil Defense Administration, You Can Beat the A-Bomb, 1:50-2:06.

[12] Federal Civil Defense Administration, You Can Beat the A-Bomb, 3:40-4:08.

[13] Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, The Family Fallout Shelter, Pamphlet MP-15, 2.

[14] Federal Civil Defense Administration, You Can Beat the A-Bomb, 0:00-1:00.

[15] Federal Civil Defense Administration, You Can Beat the A-Bomb, 2:10-2:12.

[16] Sarah A. Lichtman, “Do-It-Yourself Security: Safety, Gender, and the Home Fallout Shelter in Cold War America,” 39, 42.

[17] Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, The Family Fallout Shelter, Pamphlet MP-15, Civil Defense Information.

[18] Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, The Family Fallout Shelter, Pamphlet MP-15, 2.

[19] Sarah A. Lichtman, “Do-It-Yourself Security: Safety, Gender, and the Home Fallout Shelter in Cold War America,” 39.

[20] Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, The Family Fallout Shelter, Pamphlet MP-15, 6.

[21] Federal Civil Defense Administration, You Can Beat the A-Bomb, 5:10-9:48.

[22] Brett Spencer, "From Atomic Shelters to Arms Control: Libraries, Civil Defense, and American Militarism during the Cold War," Information and Culture 49, no. 3 (2014): 353, JSTOR.

[23] Federal Civil Defense Administration and National Education Association, Duck and Cover.

[24] Federal Civil Defense Administration and National Education Association, Duck and Cover, 0:00-0:35.

[25] Federal Civil Defense Administration and National Education Association, Duck and Cover, 1:20-2:08.

[26] Federal Civil Defense Administration and National Education Association, Duck and Cover, 2:35-2:45.

[27] Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, The Family Fallout Shelter, Pamphlet MP-15, 11, 15, 17.

[28] Federal Civil Defense Administration, You Can Beat the A-Bomb, 5:10-9:48.

[29] Sarah A. Lichtman, “Do-It-Yourself Security: Safety, Gender, and the Home Fallout Shelter in Cold War America,” 39, 40, 49.

[30] Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, The Family Fallout Shelter, Pamphlet MP-15, 17.

[31] Sarah A. Lichtman, “Do-It-Yourself Security: Safety, Gender, and the Home Fallout Shelter in Cold War America,” 40.

[32] Northcutt, “Women and The Bomb,” 133.

[33] Northcutt, “Women and The Bomb,” 129, 133.

[34] Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization, The Family Fallout Shelter, Pamphlet MP-15, 2.

[35] Masco, “Life Underground: Building the Bunker Society,” 19.

[36] Federal Civil Defense Administration and National Education Association, Duck and Cover, 0:25-0:35.

[37] Federal Civil Defense Administration and National Education Association, Duck and Cover, 5:07-6:37.

[38] Federal Civil Defense Administration, Alert Today, Alive Tomorrow, Directed by Larry O’Reilly, Film (Washington, DC: Federal Civil Defense Administration, 1956).

[39] Federal Civil Defense Administration, Alert Today, Alive Tomorrow, 0:24-1:57.

[40] Federal Civil Defense Administration, Alert Today, Alive Tomorrow, 5:33-5:47.

Comments