Icarus: A Novel and Biologically Plausible 5-Factor SNN Training Rule

- Alex Zhang

- 13 minutes ago

- 20 min read

Abstract—Spiking neural networks (SNNs) are known for their potential for massively efficient computing using specialized neuromorphic chips. Another motivation behind the development of SNNs is their biological plausibility; biological neural networks (BNNs) transmit signals in spikes, an aspect that classical artificial neural networks (ANNs) fail to replicate but SNNs display. However, current biologically plausible methods for training these networks are underdeveloped. The current standard biologically plausible training rule, reward-modulated spike-timing-dependent plasticity (RSTDP), is not robust enough to be used in most deployment scenarios; its performance is often inferior compared to biologically implausible methods such as surrogate gradients and ANN to SNN conversion. RSTDP is slow, purely local, and fragile in non-stationary environments. This paper presents Icarus, a novel, biologically inspired learning rule that extends RSTDP’s three factors into five. Icarus introduces modulating factors based on neuromodulators acetylcholine (ACh) and norepinephrine (NE), which modulate learning rate and random noise, respectively. Deployed on the actor of a spiking actor-critic system, systems trained using Icarus achieved better performance on non-stationary versions of RL benchmarks Switch Bandit and Cartpole, paving way for a more adaptable generation of SNN deployment trained using Icarus. A key limitation of Icarus is its benchmarking; it could be evaluated on a wider variety of benchmarks to make results more robust. Despite this limitation, Icarus still demonstrates that biologically-inspired neuromodulation increases the adaptability of SNNs in non-stationary environments.

Index Terms—spiking neural network, biologically plausible computing, neuromorphic computing, RSTDP, Hebbian learning

I. INTRODUCTION

Spiking neural networks (SNNs) are neural networks that encode information using discrete spike events rather than continuous-valued activations, as used by classical artificial neural networks (ANNs) [1]. Due to their event-driven nature, SNNs have the potential to perform significantly more efficiently, particularly when deployed on specialized neuromorphic computing hardware [2]. Since computation occurs only when spike events are generated, SNNs avoid the dense, synchronous activation characteristic of classical ANNs, leading to improved energy efficiency on neuromorphic platforms [3].

Typical training methods fall in three different categories. The use of surrogate gradients is widely popular due to their scalability. First developed by Hunsberger and Eliasmith in 2016 and later formalized by Neftci et al. in 2019, surrogate gradients convert the discrete spikes of a spiking neural network into continuous, differentiable gradients, allowing backpropagation to be run [4], [5]. Another training method deploys an ANN-SNN conversion, first introduced by Diehl et al. in 2015 [6]. This method involves first training an ANN using backpropagation and subsequently mapping the weights of the ANN to an SNN’s spiking rates [6]. Both of these methods are quite effective, but neither are biologically plausible [7]. Biological brains do not use gradients to strengthen/weaken synapses, and they definitely do not train and convert from ANNs [7]. A more biologically plausible method is spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) [8]. First formalized for SNNs in the year 2000 by Song, Miller and Abbott, STDP measures the relative timings between neurons to adjust weights, inspired by biological Hebbian learning processes [9], [11]. To expand this process to reinforcement learning tasks, Razvan V. Florian developed reward-modulated spike-timing-dependent plasticity (RSTDP), mimicking biological dopamine [10], [12].

A commonly noted limitation of canonical reward-modulated STDP (RSTDP) is its limited robustness in non-stationary environments, such as those encountered in many live deployment scenarios. RSTDP is typically formulated for stationary or slowly varying reward contingencies and relies on a single global dopamine-like modulatory signal, which can lead to continual weight drift, forgetting of prior mappings, or degraded performance when task dynamics change. While RSTDP captures an important aspect of biological learning through reward-dependent plasticity, it represents a simplified abstraction of neuromodulatory control in the brain. Biological learning is shaped by the interaction of multiple neuromodulatory systems, including dopamine, acetylcholine (ACh), and norepinephrine (NE), which are thought to regulate learning rate, uncertainty, attention, and exploration, particularly in volatile environments. The absence of these additional modulatory influences in standard RSTDP formulations limits their ability to flexibly adapt to changing task conditions. As a result, RSTDP captures only a narrow subset of the mechanisms underlying biological learning, motivating the development of extended learning rules that incorporate additional neuromodulatory factors to improve adaptability and stability in non-stationary settings.

To address the lack of biological robustness and the non-stationarity problem, this paper introduces Icarus, an extension of RSTDP that incorporates modulation of the learning rate and injected noise levels, emulating biological acetylcholine (ACh) and norepinephrine (NE), respectively. Specifically, ACh adaptively scales synaptic plasticity to enable rapid re-learning when the environment changes, while NE adaptively scales stochasticity in action selection to encourage targeted exploration during periods of uncertainty. Each depends on a surprise factor, which is determined by the error of the critic’s predictions. Surprise is derived from the temporal-difference (TD) prediction error produced by the critic, and is used as a single, task-change-sensitive control signal that jointly regulates plasticity (ACh) and exploration (NE). Icarus is applied only to the actor’s synaptic updates, preserving a local, online learning rule for the spiking policy network while treating the critic as a value-estimation component that supplies the TD-error signal. We focus on biologically inspired actor plasticity; the critic is used to supply a TD-error signal. Thus, deployed on the actor of a spiking actor-critic system, systems trained using Icarus achieved better performance on non-stationary versions of RL benchmarks Switch Bandit and Cartpole, paving the way for a more adaptable generation of SNN deployment trained using Icarus.

Across multiple random seeds and with controlled hyperparameter settings, Icarus consistently improves post-switch adaptation relative to baseline RSTDP and to single-factor variants that modulate only learning rate (ACh-only) or only noise (NE-only), supporting the hypothesis that jointly coupling plasticity and exploration is critical for robust non-stationary learning. One key limitation of this paper is its limited benchmarking of Icarus; nonetheless, it demonstrates that neuromodulation can enhance the performance of SNNs in non-stationary environments. In addition, we provide ablations and statistical testing to reduce the likelihood that gains are attributable to tuning artifacts.

II. RELATED WORK

A. Online and Local Learning for SNNs

Recently, many works have sought after biological plausibility with their learning rules. In 2020, Bellec et al. introduced Eligibility Propagation (e-prop), which utilizes eligibility traces in conjunction with a learning signal (typically error-related) to strengthen/weaken connections [13]. Furthermore, Deep Continual Local Learning (DECOLLE), introduced by Kaiser, Mostafa, and Neftci in 2020, uses synthetic gradients in a more local manner than classical backpropagation [14]. Very recently, Tihomirov et al. deployed an actor-critic system on RL benchmarks CartPole and Acrobot, training the actor on RSTDP and the critic on temporal difference long-term potentiation (TD-LTP), a similar local learning rule to RSTDP. Though they used Ising neuron models, a less biologically plausible neuron model, Tihomirov et al. demonstrates that RSTDP can solve CartPole reliably [15].

B. Neuromodulation, Credit Assignment, and Meta-Learning of Plasticity

Beyond a single global reward signal, recent work has explored more robust modulatory structures for credit assignment in SNNs. Liu et al. (2021) introduced a framework where modulatory signals are used to improve how recurrent spiking networks assign credit over time [16]. Furthermore, Schmidgall and Hays (2023) introduced Meta-SpikePropamine, where neuromodulated plasticity rules are learned using gradient descent [17].

C. Neuromodulators for Uncertainty and Exploration

In classical computational neuroscience, ACh and NE are often said to represent levels of uncertainty. Yu and Dayan (2005) argued that ACh tracks expected uncertainty (noise within a context), while NE tracks unexpected uncertainty (for example, an unexpected environment switch), which can trigger rapid changes in inference and learning [18]. Complementing this, Aston-Jones and Cohen proposed the LC-NE adaptive gain theory in 2005, linking NE dynamics to shifts in exploration and exploitation [19]. These theories motivate the use of surprise signals to modulate both plasticity (ACh) and exploration (NE).

III. THE ICARUS SYSTEM

As a training method, Icarus has five factors: (i) presynaptic eligibility z, (ii) postsynaptic spikes S, (iii) TD error δt, (iv) ACh-modulated learning rate εACh( n̄), and (v) NE-modulated exploration noise σNE( n̄). We next specify the neuron dynamics, surprise, neuromodulator mappings, and the resulting actor and critic update rules used in our experiments. Specific hyperparameters are shown in Table I.

A. Network Architecture

Icarus was deployed on a critic-actor system, roughly following the previous work of Tihomirov et al. [15], though we use the standard leaky-integrate-and-fire (LIF) neuron model with a modification to incorporate NE. The state of each neuron in the actor is defined by the following equations:

zi[t] = λzi[t −1] + xi[t]

λ = e−∆t/τm

vk[t] = Σ_i Wik zi[t] + ηk[t]

pk[t] = 1 −exp −ρ0 exp vk[t]−θ κ ∆t .(1)

In Eq. 1, t denotes the timestep with step size ∆t. Each input neuron i emits a binary spike xi[t] ∈{0, 1}, which is integrated by a leaky trace zi[t] that decays with factor λ = e−∆t/τm, where τm is the membrane time constant. The activity driving each output unit k is given by the noisy membrane drive vk[t] = Σ_i Wik zi[t] + ηk[t], where Wik is the synaptic weight from input neuron i to output unit k and ηk[t] is an additive noise term governed by NE. The instantaneous spiking probability pk[t] is computed as shown, where ρ0 sets the baseline firing-rate scale, θ defines the effective membrane threshold at which firing becomes likely, and κ controls the steepness with which firing probability increases as the membrane potential exceeds threshold. Output spikes are then sampled stochastically according to pk[t] and mapped to a discrete action. When both output units spike or neither spikes within a timestep, the action is selected as arg maxk vk[t], ensuring a unique action is chosen at each timestep. The actor is a single-layer spiking policy with no hidden layer, mapping encoded input spikes directly to two output neurons.

The critic neuron model is defined similarly, operating on the same spike-based state representation and leaky temporal dynamics. Input spikes are integrated through weighted synapses into a membrane variable with LIF-style dynamics, and spiking activity is generated via a thresholding mechanism. The critic produces a scalar value estimate for the current state, along with an associated uncertainty measure, both derived from the spiking hidden representation. For Switch CartPole, the critic uses a single spiking hidden layer (LIF) and two readout heads producing V(st) and σ2(st); σ2(st) is constrained to be positive via a softplus nonlinearity with a small additive floor.

B. Benchmarks

We evaluate Icarus on two non-stationary reinforcement learning benchmarks designed to test rapid adaptation under abrupt changes in task structure: Switch CartPole and Switch Bandit.

Switch CartPole: Switch CartPole is a modified version of the standard CartPole task in which the action–environment mapping is inverted halfway through training. During the first phase, actions correspond to their standard effects on the cart; after the switch, the same actions produce the opposite effects, requiring the agent to detect the change and relearn the policy. The continuous CartPole state st = (x, ẋ, θ, θ̇) is converted into a population-based spiking representation using fixed Gaussian place cells. Place-cell centers are arranged on a Cartesian grid over the state space, and each cell produces spikes according to a Poisson process with rate ri(st) = ρPC exp − (st,d −µi,d)2 / (2σ2d), where µi is the preferred state of neuron i and σd is determined by the grid spacing along dimension d. In our implementation, centers are placed on a fixed grid over each state dimension (Table I), and σd is set from the corresponding grid spacing. Rates are converted to per-timestep spike probabilities and sampled independently, yielding a sparse, distributed spike vector that serves as the input to both actor and critic networks.

Switch Bandit: Switch Bandit is a minimal non-stationary multi-armed bandit task. At each episode, the agent selects one of two actions and receives a reward if the correct arm is selected. Selecting the optimal arm yields a guaranteed reward, and selecting a suboptimal arm yields a guaranteed punishment, and the optimal arms are swapped at the switch (Table I). Non-stationarity is introduced by swapping the correct arm with the incorrect arm. This task removes state dynamics and temporal credit assignment, isolating the agent’s ability to detect changes in reward trends and adapt its policy accordingly.

Benchmark Selection Rationale: Icarus was evaluated on two complementary non-stationary benchmarks designed to isolate distinct sources of distribution shift while remaining widely used and easily reproducible. Switch Bandit provides a minimal setting with no state dynamics. The task change corresponds to an abrupt remapping of reward contingencies; this isolates the core question of whether surprise-gated neuromodulation accelerates re-learning after a latent change-point without confounds from system stability or long-horizon credit assignment. Switch CartPole introduces continuous state dynamics and closed-loop control, where the switch alters the effect of the policy on the environment, stressing both exploration and rapid plasticity under destabilizing feedback. Together, these tasks form lightweight but meaningful benchmarks spanning pure reward nonstationarity and dynamics/policy nonstationarity, enabling clear attribution of post-switch adaptation to Icarus’s plasticity–exploration modulation.

C. Training Methods and Neuromodulation

Training proceeds online at each timestep using a spike-based actor–critic framework. The critic is trained to estimate both the state value and an associated uncertainty, while the actor is trained via a neuromodulated plasticity rule. All updates are performed at the timestep level.

Surprise: Icarus bases its neuromodulation on a surprise signal derived from the novelty of the temporal-difference (TD) error. At each timestep, we define a TD-derived signal ut = |δt|. This signal is passed through two exponential moving averages with different timescales:

ft = (1 −αf) ft−1 + αf ut, st = (1 −αs) st−1 + αs ut,(2)

where ft is a fast trace capturing recent deviations and st is a slow trace representing the long-term baseline. Surprise is defined as the rectified difference between the fast and slow traces,

nt = max(0, ft −st −m),(3)

where m is a small dead-zone margin that suppresses sensitivity to minor fluctuations. To obtain a stable control signal for neuromodulation, this novelty measure is further smoothed using an exponential moving average,n̄t = βn̄t−1 + (1 −β) nt,(4)

with β close to one. In our implementation, ut is clipped to a fixed maximum for stability, and the traces are initialized on the first timestep by setting ft = st = ut (Table I).

Actor Training: The actor trains according to an extended RSTDP defined as:

∆Wik = εACh δt zi[t] Sk[t],(5)

The learning rate εACh is defined as a logistic function of the average surprise signal:

εACh = εmax / (1 + exp −kACh(n̄t −cACh)) + εbase,(6)

In Eq. 5, ∆Wik denotes the change in synaptic weight from input neuron i to output neuron k, δt is the TD error provided by the critic at timestep t, zi[t] is the presynaptic eligibility trace (Eq. 1), and Sk[t] ∈{0, 1} is the postsynaptic spike of output neuron k. The learning-rate term εACh is modulated by ACh and defined by Eq. 6, where n̄t is the exponentially smoothed surprise signal, εmax sets the maximum learning-rate contribution, kACh controls the steepness of the logistic modulation, cACh defines its activation center, and εbase is a small baseline learning rate ensuring nonzero plasticity in the absence of surprise. For stability, synaptic weights are maintained within a bounded range in our implementation.

Norepinephrine Modulation: In addition to modulating synaptic plasticity via acetylcholine, Icarus uses norepinephrine (NE) to regulate exploration in the actor. NE is computed as a logistic function of the same average surprise signal n̄t used for ACh, ensuring that a common measure of unexpected change in task dynamics drives both neuromodulators. Elevated NE increases the magnitude of additive noise in the actor’s membrane drive, thereby promoting stochastic action selection and exploration when the agent encounters novel or non-stationary conditions. As surprise diminishes and the agent adapts to the new regime, NE levels decrease, reducing noise and allowing behavior to stabilize around the learned policy. We set the noise standard deviation as:

σNE(n̄t) = σmax / (1 + exp −kNE(n̄t −cNE)) + σ0,(7)

and sample ηk[t] ∼ N(0, σNE(n̄t)2) independently for each output unit and timestep (with σNE clipped to a fixed maximum in implementation). Here, σmax sets the maximum NE-driven noise contribution, kNE controls the steepness of the logistic modulation, cNE defines its activation center, and σ0 is a small baseline noise term.

Switch CartPole Critic Training: For Switch CartPole, the critic is trained at each timestep to estimate both the state value and an associated uncertainty. Given the spike-encoded state at timestep t, the critic produces a scalar value estimate V(st) and a variance estimate σ2(st). A temporal-difference (TD) target is computed as:

yt = rt + γV(st+1),(8)

where rt is the reward and γ is the discount factor; for terminal states, V(st+1) is set to zero. In implementation, V(st+1) is computed via a forward evaluation of the critic without permanently advancing its internal spiking state buffers. The TD error is then defined as:

δt = yt −V(st).(9)

The critic is optimized using a combined loss consisting of a value regression term and a variance regression term. The value loss penalizes the squared TD error:

LV = δt2,(10)

while the variance loss encourages the predicted uncertainty to match the squared TD error:Lσ2 = (σ2(st) −δt2)2.(11)

The total critic loss is given by:

Lt = LV + Lσ2. (12)

To modulate the critic’s plasticity, the total loss is scaled by an acetylcholine-dependent factor:Lscaledt = λACh Lt,(13)

where λACh is a bounded function of the current ACh level. We define:

λACh = max(λmin, min(λmax, 1 + (εACh(n̄)/εmax)(λmax −1))), (14)

where εACh(n̄) denotes the ACh-modulated learning signal and εmax its maximum value. This scaling effectively adjusts the critic’s learning rate in response to task uncertainty while maintaining stable optimization. Gradient-based updates are applied at each timestep using this scaled loss. The critic was trained using surrogate gradients to allow stable comparison with the actor’s training process; specifically, we employ a smooth surrogate derivative for the thresholding nonlinearity (Table I).

Switch Bandit Critic Training: Due to the data sparsity of the Switch Bandit task (reward is given only at the end of each episode), Icarus was evaluated with a non-spiking critic and is trained to estimate both the expected reward and an associated uncertainty at the end of each episode. Given the (fixed) bandit state, the critic outputs a scalar value estimate V(s) and a variance estimate σ2(s). Since the task is a contextual bandit with no state transitions, the temporal-difference (TD) target reduces to the immediate reward, y = r, and the TD error is δ = r −V(s). The critic is optimized using the same combined loss structure as in Switch CartPole, consisting of a squared error value loss and a variance regression loss, L = δ2 + (σ2(s) −δ2)2. Gradient-based updates are applied at each episode using this loss. In our implementation, the Switch Bandit critic is a two-hidden-layer multi-layer perceptron (MLP) with separate linear heads for value and variance (Table I).

Training Procedure and Reproducibility: All experiments were conducted using a fixed training horizon of 4000 episodes. For both Switch CartPole and Switch Bandit, task non-stationarity was introduced by applying the environment switch at episode 2000. Network parameters were initialized randomly at the start of training, and no parameters or neuromodulatory states were reset at the environment switch point. The fast and slow surprise traces, as well as the neuromodulator levels derived from them, were maintained continuously across the switch to allow the system to autonomously detect changes in task dynamics. Neuronal state variables (e.g., membrane traces) were reset at the beginning of each episode, but the neuromodulatory traces and learned synaptic weights were maintained across episodes. Training was executed on a single CPU core on an Apple M1 system, without GPU acceleration.

IV. RESULTS

Icarus was evaluated on the two aforementioned benchmarks and compared to the same system trained with classic RSTDP (with neuromodulation turned off). For the classic RSTDP-trained system trained on Switch CartPole, the learning rate was set to 5 × 10−4, and the base noise was set to 0.5. In Switch Bandit, the learning rate was set to 10−2. The individual functions of ACh and NE modulation were further ablated. Icarus was evaluated with ACh held constant and NE modulated, and subsequently with NE held constant and ACh modulated. In addition to classic RSTDP, we also evaluated a surrogate-gradient baseline trained under the same task setup to provide a gradient-based point of comparison for non-stationary adaptation.

Surrogate-gradient baseline hyperparameters: All settings of the surrogate gradient benchmark not stated here match the classic. The actor spike nonlinearity is replaced with a surrogate Heaviside function (hard threshold in the forward pass with a smooth surrogate derivative in backpropagation), using an actor threshold θsurr = 0.5. Actor weights are optimized via SGD (optimizer learning rate fixed to 1.0 and the effective step size applied through the multiplicative ε term inside the surrogate loss) instead of a local Hebbian/RSTDP update. Finally, the surrogate actor uses small-Gaussian initialization (W ∼ N(0, 0.12) for Bandit and W ∼ N(0, 0.052) for CartPole) and clamps weights to [−10, 10] after each update for stability.

A. Switch Bandit

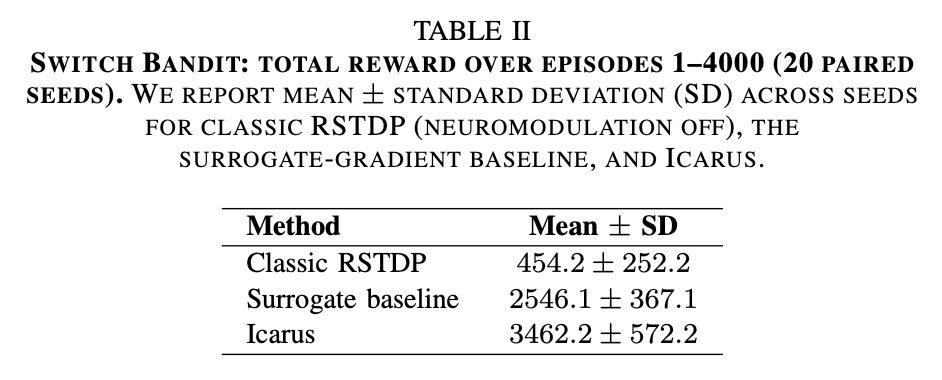

On the Switch Bandit task, Icarus significantly outperformed its classic counterpart, both in total accumulated reward and in performance after the switch. Across 20 paired seeded runs, Icarus achieved higher returns than classic RSTDP in every seed.

As shown in Table II, Icarus achieved a mean total reward of 3462.2, compared to 454.2 for classic RSTDP, corresponding to a mean paired improvement of +3008.0 across 20 seeds. This difference was statistically significant under a paired t-test (t(19) = 28.65, p < 10−16) and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (p < 10−6), indicating a robust overall advantage despite seed-to-seed variability. Relative to the surrogate-gradient baseline, Icarus also achieved significantly higher total return, corresponding to a mean paired improvement of +916.1 across 20 seeds (paired t-test: t(19) = 8.22, p = 1.11 × 10−7; Wilcoxon signed-rank: p = 9.54 × 10−6).

To isolate adaptation performance, Table III reports reward accumulated after the switch. In this regime, the performance gap widened substantially: Icarus achieved a mean post-switch reward of 1510.9, while the classic system achieved a mean reward of 1209.2. Icarus outperformed classic RSTDP in all 20 seeds, yielding a mean paired improvement of +2720.1. This improvement was statistically significant under both a paired t-test (t(19) = 25.72, p < 10−15) and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (p < 10−6). Relative to the surrogate-gradient baseline, Icarus achieved a mean post-switch improvement of +814.2 (paired t-test: t(19) = 7.39, p = 5.37 × 10−7; Wilcoxon signed-rank: p = 1.34 × 10−5).

Furthermore, Figures 1, 2, and 3 demonstrate not only a significantly faster adaptation by Icarus post-switch, but also a more stable learned policy by Icarus pre-switch.

Fig. 1. Classic RSTDP training dynamics on Switch Bandit. Mean optimal-action rate across 20 seeds using non-overlapping 50-episode windows. Shaded region denotes standard deviation. Performance collapses after the switch at episode 2000 and recovers slowly with high variability across seeds.

Fig. 2. Icarus training dynamics on Switch Bandit. Mean optimal-action rate across 20 seeds using non-overlapping 50-episode windows. Shaded region denotes standard deviation. Neuromodulation enables faster post-switch recovery and stabilization compared to classic RSTDP.

Fig. 3. Surrogate-gradient baseline training dynamics on Switch Bandit. Mean optimal-action rate across 20 seeds using non-overlapping 50-episode windows with shaded standard deviation. Performance drops sharply at the switch (episode 2000) and recovers slowly, with high across-seed variability late in training.

All three systems displayed considerable variation (Table III), but that can be attributed to the stochastic nature of spiking neural networks. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Icarus provides a substantial and consistent advantage in non-stationary bandit settings, with the largest gains observed after the switch, where rapid detection of environmental change and adaptive modulation of plasticity and exploration are critical.

B. Switch CartPole

On the Switch CartPole task, Icarus demonstrated a clear advantage in adaptation following the environment switch, though overall performance exhibited greater variability than in the Switch Bandit setting. Across 20 paired seeded runs, Icarus consistently recovered more rapidly after the switch, while classic RSTDP often accumulated higher reward prior to the switch due to greater stability in stationary dynamics.

As shown in Table IV, Icarus achieved a higher mean total reward than classic RSTDP across 20 seeds, corresponding to a mean paired improvement of +107,186.7. This difference was statistically significant under a paired t-test (t(19) = 2.83, p = 0.0107) and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (p = 0.0064). However, performance exhibited notable seed-to-seed variability, with classic RSTDP outperforming Icarus in five out of the twenty runs due to stronger pre-switch accumulation. Relative to the surrogate-gradient baseline, Icarus achieved significantly higher total return, corresponding to a mean paired improvement of +228,517.4 (paired t-test: t(19) = 4.37, p = 3.31 × 10−4; Wilcoxon signed-rank: p = 2.61 × 10−4).

To isolate adaptation performance, Table V reports reward accumulated after the switch. In this regime, Icarus substantially outperformed classic RSTDP across all 20 seeds, yielding a mean paired improvement of +241,737.7. This improvement was statistically significant under both a paired t-test (t(19) = 6.82, p < 10−6) and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (p < 10−6), indicating a consistent post-switch advantage. Relative to the surrogate-gradient baseline, Icarus achieved a mean post-switch improvement of +241,295.7 (paired t-test: t(19) = 6.82, p = 1.64 × 10−6; Wilcoxon signed-rank: p = 1.91 × 10−6).

Fig. 4. Classic RSTDP training dynamics on Switch CartPole. Mean per-episode reward across 20 seeds with shaded standard deviation. Performance is stable prior to the switch at episode 2000 but collapses sharply afterward, followed by slow and incomplete recovery.

Fig. 5. Icarus training dynamics on Switch CartPole. Mean per-episode reward across 20 seeds with shaded standard deviation. Although Icarus exhibits greater variability during training, neuromodulation enables faster post-switch recovery and sustained improvement relative to classic RSTDP.

Fig. 6. Surrogate-gradient baseline training dynamics on Switch CartPole. Mean per-episode reward across 20 seeds with shaded standard deviation. The surrogate baseline achieves stable pre-switch performance but fails to recover after the switch, remaining near-minimal reward throughout the post-switch regime.

Figures 4, 5, and 6 illustrate the averaged per-episode rewards of the three methods. While classic RSTDP and surrogate gradients achieve stable performance prior to the switch, it adapts poorly afterward. In contrast, Icarus recovers substantially faster following the switch. Figure 6 shows that the surrogate-gradient baseline similarly fails to recover after the switch, consistent with its low post-switch returns in Table V.

All methods display considerable variability, reflecting the stochastic nature of spiking neural networks and the sensitivity of CartPole dynamics. Taken together, these results indicate that Icarus trades stationary stability for improved adaptability, yielding its strongest gains in the post-switch regime where rapid detection of environmental change and adaptive modulation of plasticity and exploration are critical.

C. Ablation Study

To isolate the individual roles of acetylcholine (ACh) and norepinephrine (NE) in Icarus, we evaluated two reduced variants on the Switch Bandit task: (i) NE-only modulation, where ACh was held constant and only NE was modulated, and (ii) ACh-only modulation, where NE was held constant and only ACh was modulated.

Both ablations reliably learned the initial (pre-switch) arm, reaching near-optimal choice rates prior to episode 2000 (Figures 7 and 8). After the switch, performance collapsed for both ablations, indicating that both neuromodulators are needed for Icarus’s superior performance.

Taken together, these ablations suggest complementary roles for the two modulators in non-stationary bandit learning: ACh-mediated plasticity control is particularly important for regaining performance after the switch, while NE-mediated exploration contributes to smoother and earlier recovery trajectories. Consistent with this interpretation, the full Icarus system (ACh+NE) achieves substantially stronger and more consistent post-switch adaptation than either ablation alone.

Fig. 7. NE-only modulation (ACh held constant) on Switch Bandit. Mean optimal-action rate across 20 seeds with shaded standard deviation. Performance drops sharply at the switch (episode 2000) and recovers gradually.

Fig. 8. ACh-only modulation (NE held constant) on Switch Bandit. Mean optimal-action rate across 20 seeds with shaded standard deviation. Recovery is delayed but becomes rapid late in training, with higher across-seed variability.

V. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This paper presents a SNN training method, Icarus, that utilizes biologically inspired neuromodulation. Its superior performance in non-stationary environments was demonstrated using the Switch CartPole and Switch Bandit, paving the way for more biologically plausible training of SNNs. Icarus significantly outperformed its classic counterpart in Switch Bandit, while Icarus’s improvements on Switch CartPole were more varied. Nonetheless, Icarus has shown superior performance on these non-stationary tasks. Furthermore, the ablations demonstrated the complementary nature of the two neuromodulatory signals; neither ACh nor NE alone can result in Icarus’s superior performance.

An important limitation is the benchmarking. More rigorous benchmarking on harder environments and varied SNN systems (more complex critics/actors) would make Icarus’s contributions more robust. Additionally, Icarus was evaluated on a system with biologically implausible critics; the Switch CartPole critic was trained using surrogate gradients, and the Switch Bandit critic was an MLP. These biological implausibilities were implemented to produce a fair and stable comparison between classical RSTDP and Icarus’s training on the actor, but future work can implement Icarus on a fully spiking and biologically plausible system.

REFERENCES

[1] W. Maass, “Networks of spiking neurons: The third generation of neural network models,” Neural Networks, vol. 10, no. 9, pp. 1659–1671, 1997, doi: 10.1016/S0893-6080(97)00011-7.

[2] G. Indiveri and S.-C. Liu, “Memory and information processing in neuromorphic systems,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 103, no. 8, pp. 1379–1397, 2015, doi: 10.1109/JPROC.2015.2444094.

[3] M. Davies et al., “Loihi: A neuromorphic manycore processor with on-chip learning,” IEEE Micro, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 82–99, 2018, doi: 10.1109/MM.2018.112130359.

[4] E. Hunsberger and C. Eliasmith, “Training spiking deep networks for neuromorphic hardware,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.05141, 2016.[5] E. O. Neftci, H. Mostafa, and F. Zenke, “Surrogate gradient learning in spiking neural networks,” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, vol. 36, no. 6, pp. 51–63, 2019, doi: 10.1109/MSP.2019.2931595.

[6] P. U. Diehl, D. Neil, J. Binas, M. Cook, S.-C. Liu, and M. Pfeiffer, “Fast-classifying, high-accuracy spiking deep networks through weight and threshold balancing,” in Proc. 2015 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 2015, pp. 1–8, doi: 10.1109/IJCNN.2015.7280696.

[7] T. P. Lillicrap, A. Santoro, L. Marris, C. J. Akerman, and G. Hinton, “Backpropagation and the brain,” Nature Reviews Neuroscience, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 335–346, 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41583-020-0277-3.

[8] G.-Q. Bi and M.-M. Poo, “Synaptic modifications in cultured hippocampal neurons: dependence on spike timing, synaptic strength, and postsynaptic cell type,” Journal of Neuroscience, vol. 18, no. 24, pp. 10464–10472, 1998, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10464.1998.

[9] S. Song, K. D. Miller, and L. F. Abbott, “Competitive Hebbian learning through spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity,” Nature Neuroscience, vol. 3, no. 9, pp. 919–926, 2000, doi: 10.1038/78829.

[10] R. V. Florian, “Reinforcement learning through modulation of spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity,” Neural Computation, vol. 19, no. 6, pp. 1468–1502, 2007, doi: 10.1162/neco.2007.19.6.1468.

[11] D. O. Hebb, The Organization of Behavior: A Neuropsychological Theory. Wiley, 1949.

[12] E. M. Izhikevich, “Solving the distal reward problem through linkage of STDP and dopamine signaling,” Cerebral Cortex, vol. 17, no. 10, pp. 2443–2452, 2007, doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl152.

[13] G. Bellec, F. Scherr, A. Subramoney, E. Hajek, D. Salaj, R. Legenstein, and W. Maass, “A solution to the learning dilemma for recurrent networks of spiking neurons,” Nature Communications, vol. 11, art. 3625, 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17236-y.

[14] J. Kaiser, H. Mostafa, and E. O. Neftci, “Synaptic plasticity dynamics for deep continuous local learning (DECOLLE),” Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 14, art. 424, 2020, doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00424.

[15] Y. Tihomirov, R. Rybka, A. Serenko, and A. Sboev, “Combination of reward-modulated spike-timing dependent plasticity and temporal difference long-term potentiation in actor-critic spiking neural network,” Cognitive Systems Research, vol. 90, art. 101334, 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.cogsys.2025.101334.

[16] Y. H. Liu, S. Smith, S. Mihalas, E. Shea-Brown, and U. Sümbül, “Cell-type-specific neuromodulation guides synaptic credit assignment in a spiking neural network,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 118, no. 51, e2111821118, 2021, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2111821118.

[17] S. Schmidgall and J. Hays, “Meta-SpikePropamine: learning to learn with synaptic plasticity in spiking neural networks,” Frontiers in Neuroscience, vol. 17, art. 1183321, 2023, doi: 10.3389/fnins.2023.1183321.

[18] A. J. Yu and P. Dayan, “Uncertainty, neuromodulation, and attention,” Neuron, vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 681–692, 2005, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.026.

[19] G. Aston-Jones and J. D. Cohen, “An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance,” Annu. Rev. Neurosci., vol. 28, pp. 403–450, 2005, doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709.

Comments